Will women’s demand for rights be met in the system by a prosecutor or judge “doing her/his job well”, “taking initiative”, “good-hearted”, “making an effort”, “being conscientious enough to be grateful for”? Is the legal guarantee that the legal system can offer women for our rights to have the chance to come across a good person?

Consider a prosecutor, in a request for arrest for a man who used violence against a woman, referring to the right of “all women to live freely, be on the street and go on with their lives.” “The streets, the subways, should be full of trust, not fear,” he says with a manifesto-like expression. She is convinced that in an order where a woman is not free, women are not free.

Consider a female judge in a case about a woman’s sexuality in a human rights court. Against the gender and age-discriminatory view of another judge on women’s sexuality, she is saying “If such ignorant judgments come not from writers but from judges, the consequences are more worrying.” With her words, she slams his intervention in injustice in the face of sexist ignorant judges.

Do you think that if all the judges and prosecutors we meet had this awareness, ethics and qualifications, wouldn’t the world be a place where we would be stronger against injustices?

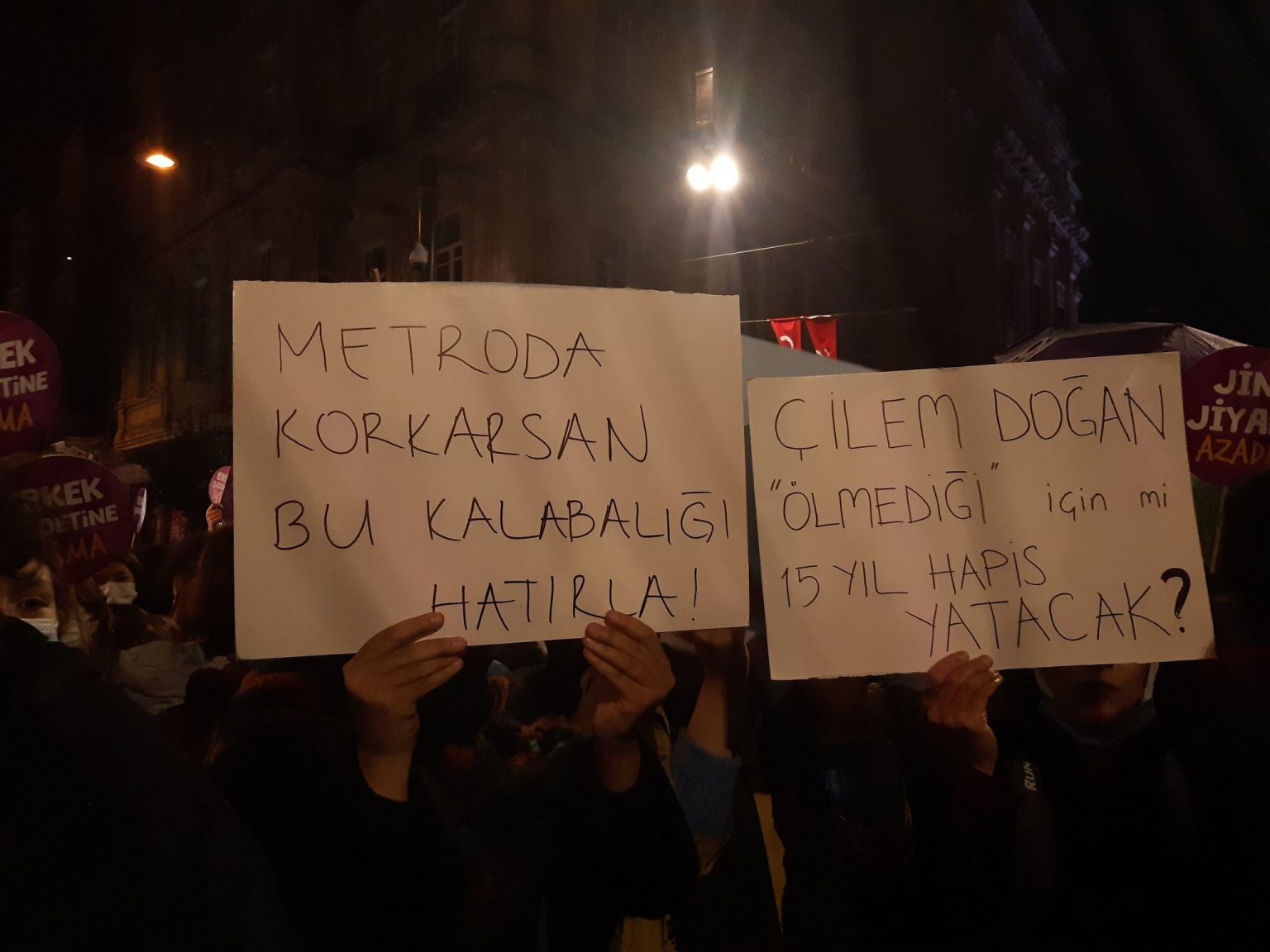

This year, on 25 November, the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, another event took place apart from the fact that tens of thousands of women filled the areas in many provinces. We witnessed another incident of a man stalking and threatening a woman with a knife in the Istanbul Tavşanlı Subway, the ease of the act of “killing” for violent men, and the reality and immediacy of the fear and threat of being killed for women. “Tavşanlı Subway” became the agenda of 25 November on social media.

What attracted more attention than the act of violence was the determinations and phraseology, the words used by the Public Prosecutor Fatmagül Yörük in the arrest warrant, regarding the violence and the meaning and consequences of the perpetrator’s actions. The determinations of the dear public prosecutor are a good example of violence against women and that the decisions to be taken in the legal arena means an intervention and organization in the social justice order.

Even though I was touched with a sense of relief when I read Fatmagül Yörük’s request for arrest, it’s hard not to be saddened by the threat posed by the fact that the “rights” for women in Turkey, which have been going on for the last few years and intensified in 2021, have been deleted from the positive legal texts, the fact that they are actually abolished, eroded, and the methods with which usurpation of rights has been covered up with rhetoric, caused to forget and normalized, and the overwhelming size of a prosecutor’s “effort.”

Will women always use mechanisms in their pursuit of rights in their lives, hoping to encounter a prosecutor, judge or decision maker like Fatmagül Yörük? Will women’s demand for rights be met in the system by a prosecutor or judge “doing her/his job well”, “taking initiative”, “good-hearted”, “making an effort”, “being conscientious enough to be grateful for”? Is the legal guarantee that the legal system can offer women for our rights to have the chance to come across a good person?

Although the questions are pessimistic, I wrote this article with the motivation to understand and explain the modifier and transformative function of the arrest warrant written by Fatmagül Yörük. Legal texts, that are mostly copies of each other, contain justifications written by referring only to laws and written texts. At this point, It is possible to discuss that how brave and eager are the judges and prosecutors, the ones who are in the decision-making position in the legal system, to intervene in injustices through their decisions; both ethically and qualitatively. (I will explain this eagerness and dealing with injustice below.)

There are some manifesto-like decisions of prosecutors/judges

Fatmagül Yörük, in her warrant of arrest, basically touches on some issues in a way of expression that we are not accustomed to in legal texts. The prosecutor’s narrative, justification, and ultimately her demand draws the case from an individual threat and offers a possible explanation for the interpretation that “if you threaten a woman in public with a knife in your hand, there is a threat of death, this threat is perfectly rational, it is very likely to happen.”

When judges and prosecutors turn a blind eye to the inequality and power relations in the society during the decision stage, for example, when they do not think or know that a woman is oppressed because she is a woman and what the forms of oppression might be, when they cannot empathize or they look at a woman with a sexist traditionalist lens, when they do not see that “she is a woman” in the home where the woman is subjected to violence or in the society where she is discriminated, they make unfair decisions. How does this injustice become manifest? They do not believe what the woman tells, they do not take it seriously, they think that she is exaggerating, and they empathize with the perpetrator by thinking that the perpetrator of violence may have been angry, gone mad, or provoked. In the cases where women are oppressed, they ignore the systematicity in the society in the cases that come before them, and build their decisions by placing everything in an individual corner in the case.

Fatmagül Yörük says that the threat a woman faces is a crime against the freedom of all women. We can prevent violence by enforcing the law, she says, protecting women’s right to life and leaving a secure future for girls is the primary duty of the whole society.

The way she expresses her determinations about injustice is also a strong opposition to the thoughts and beliefs that cause injustice. The elocution against this injustice reminded me of a few judgments of the judges that made me smile as I read them earlier.

One of these was a case brought against the Portuguese state in 2017 at the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), which discriminated against a woman through thoroughly sexist judgement processes in which the sexuality of a fifty-year-old woman was debated. You can reach the details of this case and the decisions of the ECtHR from this link.

In summary, a decision was made in Portugal that equated women’s sexuality with their fertility, and without measure, it was discussed whether a 50-year-old woman had sexuality. The ECtHR ruled that the Portuguese courts’ decisions were discriminatory.

Two women judges at the ECtHR agreed with the decision and wrote a concurring opinion. The concurring opinion, including literary references written by ECtHR judges Yudkivska and Motoc, is like a walking manifesto.

Judge Yudkivska begins her opinion writing of agreeing with the decision with quotations from Tolstoy’s Kreutzer Sonata and Jean Jacques Rousseau’s Emile.

“The absence of the rights of woman does not consist in the fact that she has not the right to vote, or the right to sit on the bench, but in the fact that in her affectional relations she is not the equal of man (…) They excite woman, they give her all sorts of rights equal to those of men, but they continue to look upon her as an object of sensual desire, and thus they bring her up from infancy and in public opinion.” (Tolstoy, The Kreutzer Sonata)[1]

“Has not a woman the same needs as a man, but without the same right to make them known?” (Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Emile)[2]

Quoting Tolstoy and Rousseau, Yudkivska continues:

“When Anton Chekhov read Tolstoy’s The Kreutzer Sonata, he was astonished, being a doctor by education, by how little the ‘Titan’ of Russian literature knew about women’s sexuality. According to Chekhov, Tolstoy’s judgments in this respect ‘are not only questionable, but also clearly betray an ignorant person who has not even bothered to read two or three books written by specialists. If such ignorant judgments come not from writers but from judges, the consequences are more worrying. Tolstoy had done nothing more or less than reproduce the stereotypes developed for centuries in patriarchal societies about the essence of women and their corresponding role. These stereotypes should never come from a courtroom.”[3]

“For centuries a woman’s entire life was confined to the production of children and to their care. ’Kinder, Küche, Kirche’ as the only permissible areas for female activity. A woman was not respected as a human being. Her desires were ignored. (…) She was just a reproductive machine (in some old dictionaries it is even argued that the very word “woman” in English derives from “man with a womb”).”[4]

“In the following paragraphs, Judge Yudkivska refers to the words of a sexist judge in the US Supreme Court’s decision to reject a woman’s application for a license to work as a lawyer in the 1880s, and reminds the Portuguese courts that the 1880s are far behind. “The US Supreme Court often quotes from Justice Bradley’s infamous concurring opinion in the case of Bradwell v. Illinois, as an example of how harmful stereotypes infected judicial reasoning in the past and to remind us to always remain vigilant against them. Justice Bradley referred to the separate spheres of men and women and how ‘[t]he paramount destiny and mission of woman are to fulfil the noble and benign offices of wife and mother. This is the law of the Creator’. Fortunately, most court systems have come a long way since then, and yet are there not echoes of this pervasive stereotyping in the judgment of the Supreme Administrative Court of Portugal?”[5]

“There is a great temptation to believe that all of these millennia-old social stereotypes, persistent ideas and practices are nowadays just ‘water under the bridge’, at least in Europe. Unfortunately, they are not. Even in 21st century Europe, age-old prejudices may rear their ugly heads. In the present case, it is clear that out-dated gender stereotypes have influenced a judicial decision (…) In other words, the Supreme Administrative Court, in the best patriarchal traditions, connected the woman’s sexual life with procreation. This was precisely the point at which gender-based discrimination occurred.”[6]

In the same case, the other judge Motoc, in her opinion, emphasizes the importance of understanding and naming stereotypes about women. “Stereotypes are also attempts at categorisation that we use in everyday life. There is no explicit or agreed legal definition of stereotypes. In the context of gender discrimination, the definition proposed by Rebecca Cook and Simone Cusack is widely accepted: ‘A stereotype is a generalized view or preconception of attributes or characteristics possessed by, or the roles that are or should be performed by, members of a particular group.’”[7]

While expressing that freedom will only be possible with the elimination of prejudices and stereotypes, he also referred to the US feminist lawyer Catharina MacKinnon who says “You can’t change a reality you can’t name.” And what is social harm must first be identified, otherwise it will not be possible to eliminate and repair the damage. The first step is to name the stereotype.

“Stereotypes affect the autonomy of groups and individuals. For the disadvantage test it is enough to prove that the stereotypes are harmful to the group to which the applicant belongs and that the rule or practice applied by the State is based on such stereotypes. ‘Discrimination must be understood in the context of the experience of those on whom it impacts.’”[8]

Motoc concludes her opinion by citing the German Philosopher, Cornelia Klinger, “‘The devastating effects of modern man’s effort to transcend the contingency of the human condition by overpowering and dominating nature (and the human beings who are symbolically identified with nature; the nature, the savage, the child, the women) have become only too obvious at the end of the century’ (Cornelia Klinger). Gender equality is still a goal to be achieved, and addressing the deep roots of inequality in the form of stereotyping is an important means of pursuing this goal.”[9]

The duty of judges and prosecutors: To see injustice

The debate on the relationship between law and justice is a rich topic with a long history and different perspectives. It is also argued that the law is not the unfailing carrier of justice, but a fiction of fairness aimed at fulfilling people’s sense of justice, as are the views that these two are not the same, and that even the expression “justice” is not necessary in the definition of law. [1]

Aside from the debates on justice, the decisions of judges and prosecutors that I have cited above reminded me of a debate on injustice and being seen in the context of seeing and intervening in injustice.

Injustice is closely related to the concept of seeing. The concept of seeing is about being seen of person. Not being seen leads to injustice. Therefore, there is a direct relationship between seeing and injustice. Gender discrimination, racial discrimination, discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity are related to the fact that the law, the system and the fiction of fairness do not see the other person as human. [1]

Seeing injustice is not about seeing the abstract, equal rights individual and achieving this equality. Nor is it a seeing that aims to eliminate social and economic inequalities. Seeing injustice is based on an understanding that is away from disrespect and humiliation. The notion of seeing in law is based not only what justice is and what it necessitates, but also on what is to be chased after is to see injustice.. [2]

In her book Hukukta Adaletsizliği Görmek [Seeing Injustice in Law], Gülriz Uygur underlines that “desiring to achieve justice requires to see and take care in law.” Judges have an obligation to make ethical decisions and do the right thing, as they affect people’s lives. The judge’s understanding, inability to understand, or misunderstanding of the action in question is also limited by her/his own life experiences. In order to understand, the judge must connect the action, the attitudes and the conditions in which it was made to the reasons. Gülriz Uygur states that the judge, who has the ability to see injustice, must “be troubled” about the incident before her/him in order to see the injustice, and that being troubled brings “worrying” along with it. Worrying in this context, as seeing injustice, focuses on what should be done and how.

In March 2021, Turkey left the Istanbul Convention, which is one of the only legal guarantees of women’s human rights and the struggle against discrimination and violence. Since that day (in fact, since the last few years, when the attacks against the Convention and all legal documents limiting the intervention of women’s rights along with the Convention began), women have both struggled and worried against the erosion of their rights. I will refer to a decision made by the Constitutional Court in the past weeks on the issue that practitioners of law being troubled and worrying about injustice. The decision is very important in two aspects. First of all, it envisages the punishment of judges and prosecutors when a woman is near threatened of violence and is not protected by judges and prosecutors and the necessary precautions are not taken, and it has the characteristics of a case law against impunity in the world of law practitioners. Secondly, the allegory of the country about the systematicity of violence against women is described throughout the resolution, which has been written for pages, and violence becomes no longer an isolated case. However, one side of the resolution is missing related to the issue which I am trying to explain in this article about the judge seeing injustice and worrying about injustice. When we look at the section where the Istanbul Convention is mentioned in the resolution, the members of the Constitutional Court make a reference to the Istanbul Convention. The Istanbul Convention should be applied as the “relevant law” to the event before them, because the Istanbul Convention was in force at the time of the events.

However, in a current situation where women’s rights are so threatened and the means of threat is to repeal or fail to implement the Istanbul Convention, wouldn’t it be possible for high court judges to implement the Istanbul Convention -and to accept it as the relevant law on which the Law No. 6284 is taken as a reference and adopted as the principle after all- as a correspondence of being worried about injustice against women ,?

Legal texts contain a method and a form of expression suitable for the compulsory feature of law. Studies examining the relationship of law with literature and other cultural fields mention that legal rules and legal texts have to be away from fictionalities such as literature, poetry and music, which are the products of human mind, in order to legitimize itself and to be in a compulsory position. Law is the product of the common mind and is not fiction, but a tool put at the service of revealing the truth. For this reason, there is a difference between the decision makers who write legal texts, laws and decisions and the way an author uses language.

How necessary is it for judges and prosecutors, the language of the decisions I quoted above, who see injustice, to speak out from within our lives against injustice, departing from the methods appropriate to the compulsory nature of the law, and the expressions of strict borders, both for the elimination of injustice and the justice they construct where women stand.

When I read Fatmagül Yörük’s request for arrest, I was relieved because it had a message against injustice. Just as stated above, the prosecutor saw the injustice and intervened against it. She did not take refuge in the wording of the compulsory legal rules, while describing the violence, she stated that the decision was made “for the safety of all women”, and she saw the woman who was threatened, the women who were subjected to violence in this country, both in private and in public, and she saw injustice. Just as the two judges, who wrote their opinions on the ECtHR resolution, emphasized the injustice of women being squeezed into stereotypical roles for centuries…

As Judge Motoc stated, gender equality is still a goal, and while struggling to achieve it, there are judges and prosecutors who, fortunately, see injustice and write resolutions against injustice by purging the language of the cliché we know.

[1] Yalçın Armağan, “Hakkaniyet Kurmacası”, in Edebiyat, Hukuk ve Sair Tuhaflıklar, ed. Cemal Bali Akal, Yalçın Tosun,

[2] Hukukta Adaletsizliği Görmek, Gülriz Uygur

For the original in Turkish / Yazının Türkçesi için

Translator: Gülcan Ergün

Proof-reader: Müge Karahan

[1] Leo Tolstoy. The Kreutzer Sonata and Other Stories, Project Gutenberg E-books. p. 65-66 and 90.

[2] Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Emile, Project Gutenberg E-books. p.. 195.

[3] https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/fre#%7B%22itemid%22:[%22001-175659%22]%7D

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.